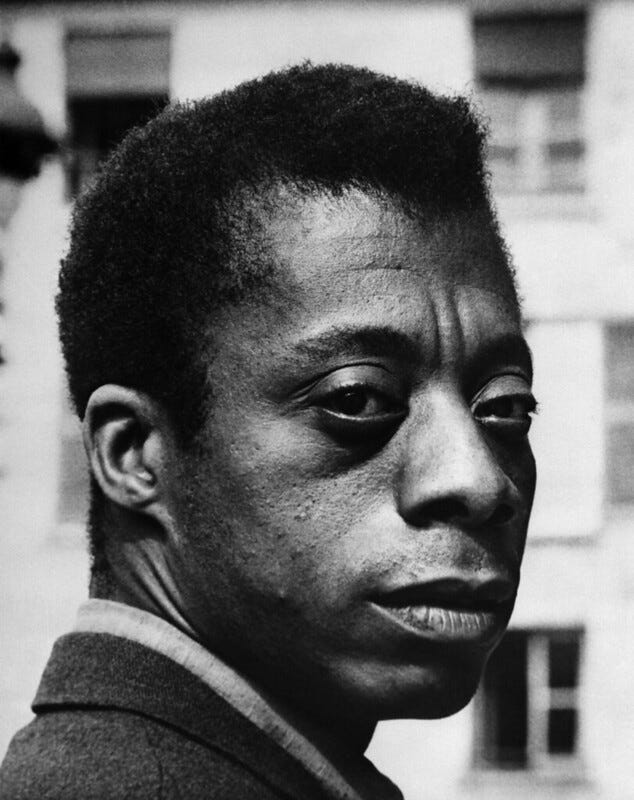

James Baldwin and DEI, the Politics of Parenting, the Evolution of Human Cognitive Abilities

Baldwin turns 100. Sapiens and the persistence of gender inequality.

James Baldwin has to be one of the most interesting public thinkers in history. He was the original “woke” figure when the word still meant enlightened. His words in the United States and overseas forced people to think deeply about the founding, beauty, and complications of our country. On his 100th birthday, we should reflect on one of his more controversial ideas that we still debate today—that we all built America.

“I am not a ward of America. I am not an object of missionary charity. I am one of the people who built the country. Until this [is accepted] there is scarcely any hope for the American dream,” Baldwin concluded during a 1965 debate against William F. Buckley, founder of the conservative National Review in the UK. Baldwin won the debate.

His rhetoric was bold and still is. His words, noting that Black and other minorities are not simply people who have taken from the state but people who have helped build it, remain controversial, though a matter of historical record as he notes.

Other authors like Nikole Hannah-Jones have come under scrutiny and had their books banned for echoing similar ideas.

Why does this idea ruffle people’s feathers?

Particularly today, there seems to be a notion that Black people are unjustly taking from the country without earning what they have received. Following the Supreme Court striking down affirmative action and the anti-DEI movement, this concept is perpetuated. We see it in references to elected officials, journalists, CEOs, and the like as “DEI” which once meant diversity, equity, and inclusion, now insinuating they didn’t earn their spots. I’ve had friends in various positions say they were attacked online with terms like “DEI.”

But Baldwin challenges this perpetuating idea that Black Americans must constantly prove themselves to belong.

“From a very literal point of view, the harbors and the ports, and the railroads of the country, the economy, especially of the southern states, could not conceivably be what it has become if they had not had… cheap labor,” says Baldwin during that debate, referencing the slaves who built the country “under someone else’s whip… for nothing.”

So what if people learn and internalize that Black and other minorities in the country have earned their spaces and have contributed to the building of this country?

This is something that theorists like W.E.B. Du Bois and Baldwin point out as important in their writings and speeches. They argue that it is crucial to see Black contributions to society—not just for making peanut butter like we often do during Black History Month, but as Baldwin notes, for the railroads or, as Hannah-Jones points out, for the realization of civil rights in the country.

Once you start from a place of believing that a minority person with a high position did something to earn it, and people see each other and their ancestors as equal contributors to the country, equally hardworking, the manner of discourse on so many issues could change.

Therefore, it goes without question that Baldwin’s thoughts are as relevant today as they were in 1965. The debate, though morphed in some ways, still rages on.

“If one has got to prove one's title to the land, isn’t 400 years enough?” asks Baldwin. “400 years, at least 3 wars, the American soil is full of the corpses of my ancestors.”

Has having kids suddenly become political?

Does anyone else think it’s... odd... that this election season the rhetoric has divided Americans between those of us who have children and those who don’t? Like many things this election cycle, I did not see that one coming.

I know a lot of people—people who aspire and don’t aspire to be parents—and none of those decisions are political. For many people I know, having children is a deeply personal, apolitical decision. For some, the choice is out of their hands; they may want kids but can’t have them or have lost them.

But I have lived in countries where bearing children is a political act for some party members. In Turkey, for example, in 2009, then Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan called on families to bear three children each as a way of securing the strength of the nation.

“Strong families lead to strong nations,” Erdoğan was quoted saying.

In Spain, political leaders have passed policies to encourage people to bear children, an effort to hedge against an aging population. But both of those countries are arguably more accommodating than the U.S. for parents. They have paid leave policies and, in Spain, public playgrounds for children are everywhere.

In America, without paid leave and with soaring childcare costs, having a kid is not always considered an economically sound decision. When I was in the State Department, several foreign service officers with young children refused to take posts in the United States because of the cost of childcare and the availability of affordable quality schools.

With this new line of discussion about parenthood in America, maybe more discussions will follow about ways to relieve parents from the burdens of having children.

What I Am Reading: Sapiens

I recently picked up the book "Sapiens" by Yuval Noah Harari, a book about the evolutionary development of human cognitive abilities. This book is as interesting as it is dry, and yes, both things can be true. But one part of the book stuck out to me: the lack of understanding about the persistence of gender inequality throughout human societies throughout time.

It’s wild because throughout the novel the author has interesting explanations for why humans are racist, why Europeans ruled the seas, why monotheistic religions became more influential than polytheistic ones, and so on. But there is no explanation for why no matter what society I was born into almost at any time in human history, if I was a woman, I would most likely be subjected to a lower class.

He then goes on to debunk common theories that people have about why this is, like strength. For example, he points out that great strength simply meant you got put on the front lines and died first, but the people actually running things were often average and smart like Napoleon. It was intelligence and the ability to govern that made leaders in societies, not strength.

But why then do we see this persistent gender inequality everywhere? Don’t women have the capability to be just as intelligent? Frustratingly, he doesn’t have a concrete answer.

This particularly struck me because I recently did a story for NPR that showed how people incarcerated in women’s prisons had less access to educational opportunities than those in men’s prisons. This is important because access to education is said to be the number one way to reduce recidivism. And just by a set of what could be described as flukes, women, even in prison, don’t have equal opportunities.

Subscribe and Share

I hope you found this newsletter helpful and engaging. Please share with any friends or family you think would be interested and feel free to buy me a coffee by subscribing if you got some use out of it.

Follow me on Instagram too!